Because Game Studies is both new and interdisciplinary, with scholars from many fields each focusing on the elements that relate to their own specialty, there are many objects of study, ranging from the technical, programming aspects and gameplay to the impact of the art and visuals, the spoken and written words, and the subculture (and economy) that has grown up around gaming. It is an exciting field to be working in, and in many instances the interdisciplinary nature allows scholars to go outside their comfort zone, to study things that are not exactly in their wheelhouse, but can be approached in a similar manner – or those that are familiar, but can be studying in a different way. Since the direction I am coming at this field is through English Studies, I will look at two of the most common approaches to study: the way narratives are constructed and the pedagogical underpinnings of using games in education

Creation and Communication of Narrative

One area of focus is the game’s narrative, or story. Of course, part of the reason games are so effective at storytelling is that they can use written and spoken text, music and sound, moving and still images and, of course, gameplay and mechanics in service of the story. Because the story is interactive, the player becomes more invested in and engaged with the story than they would as a strictly passive consumer of print or video media. Of course, different games will apply each of these elements in different ways.

One example of a game that benefits from both literary and rhetorical analysis techniques from an English Studies perspective is the Game of Thrones game

by Telltale Games. As the following video shows, the designers use the full range of cinematic tools at their disposal to tell the story, and the inclusion of voice acting from several of the TV adaptation’s lead actors increases the sense of immersion. In addition, the player has to make both dialogue and action choices along the way, as well as there being a limited skill element, where players occasionally have to rapidly touch a particular spot on the screen (to punch someone in the face, for example, or put out a fire), which adds a sense of urgency. All of these elements are ripe for exploration by scholars, and allow the application of multiple approaches and theoretical backgrounds.

Games in Education

The impact of video games on education has received a great deal of attention. As previously stated, some people have focused on superficial “gamification” tactics, but game scholars have delved much more deeply into how people learn, and how games can be both informational texts and teaching tools, either

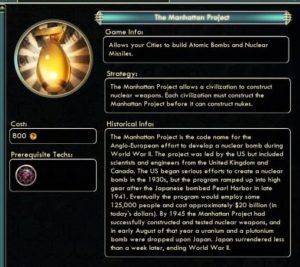

analyzing existing games as objects of study (for example, Civilization to teach history, World of Warcraft to teach economics, etc. or “literary games” as studied by Astrid Ensslin), or developing new games. While the latter is certainly an area of interest for me, it strays into more interdisciplinary territory rather thanbeing more rooted in English Studies. In defining the OoS for Education, the focus is on what skills are applicable in an academic setting that are “taught” through the medium of the game, and the means by which the game encourages mastery of those skills.

In the case of games in English education, much of what is studied relates to any form of written text accompanying the game, whether it is on screen conversations among players, “help” text, in-game signage and interface labeling, or accompanying texts (written gameplay documentation, player or company-created strategy guides, etc.). These texts can be studied to determine what content is being conveyed, what a player’s mastery of that content is, and how the delivery method – the game itself, through storyline, mechanics, graphics, etc. – contribute to the learning process. Kevin Moberly’s essay, “Composition, Computer Games, and the Absence of Writing” addresses the way that real time audio chat eventually eclipsed written chat formats in online games like Warcraft, while also addressing the rhetoric and communication going on through non-written means, through the way the player crafts an identity for their character and the choices that they make. Likewise, Alexander’s “Gaming, Student Literacies, and the Composition Classroom” explores the paratexts that evolve alongside games, including strategy guides, wikis, message boards, and other peripheral game-related texts.

History/Future

Because the field of Game Studies is so heavily dependent on technology, as new tools and platforms are developed, so too will now objects of study present themselves. Virtual Reality gaming is becoming more widespread and affordable to consumers, and the success of Pokemon Go! has renewed interest in Augmented Reality Gaming. The history of the field has largely responded to the development of new delivery platforms and new styles of gaming (strategy, FPS, story-based, hidden-object based) as their popularity ebbs and flows, and so the field will have to continue to evolve just as rapidly.

Additional Resources:

Virtual Reality Gaming

CNBC provides a quick overview of virtual reality gaming.

Augmented Reality Gaming

Though best known for her book Reality is Broken and its explorations of the potential for gamification across education and many other industries, Jane McGonigal also holds a PhD in Performance Studies from UC Berkley. Her “I Love Bees” transmedia narrative showed the potential for gaming as promotion, serious gaming, and games that go out into the world beyond the computer.

McGonigal’s TED Talk on using gaming to change the world.

Gamification

While gamification is beyond the scope of this essay, it is an important concept in both gaming and education (and draws heavily on the work of Jane McGonigal). In this video, Extra Credits reviews the advantages and disadvantages of the approach.