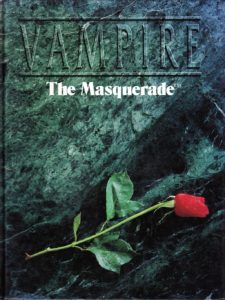

My first job after graduating from Wesleyan University was as a tabletop roleplaying game designer at White Wolf, and it was there that I developed what has remained a pillar of my own approach to game design: namely, the idea that game mechanics – the rules by which the game is played –

must meld seamlessly with the themes and setting of the game. In the game Vampire: The Masquerade, the core theme is the struggle between “The Beast” (one’s vampire nature), and one’s “Humanity.” These are primarily abstract roleplaying concepts, however, so in order to make the game more than purely narrative, the game assigns two key statistics to each character – their blood pool, and their Humanity score. Let the blood pool go too low (due to wounds, using vampiric abilities, or not feeding), and the character frenzies, loses control, and the evil acts they commit lowers their Humanity score. Of course, this is a simplification, but the core mechanic of the game supports the theme, determines the kinds of stories that will be told, and guides the player’s roleplaying.

How does this relate to epistemology? When game studies were formalized as a field of academic study, the two opposing camps were narratology and ludology – in essence, focus on story or mechanics. The latter does not preclude the presence of story in games, but it does require there to be game elements there for something to be considered a game. Of these two epistemological perspectives, I align myself more closely with narratology, as ultimately I find the story more interesting. Coming from an English studies background, that is the toolbox I am accustomed to using.

As I read more deeply on narratology, however, I recalled my own background. You can tell players that it’s important to the story to do something – retain one’s Humanity, for example – but if you do not attach a number, a game mechanic to it, they are free to ignore it. Mechanics are how you tell the player what is important, and what you want them to do. My own approach as a game designer, then, is a melding of narratology and ludology: the mechanics exist to guide the story. As a scholar of English studies, my approach is to look at the mechanics and gameplay through the lens of the story; the way that the game is played is a part of the story, whether that is the narrative being created by the game’s designer, or the self-created narrative of the player: the story of their character’s adventure in the world of the game. While not identical, my method is very similar to that of Harrison Pink, who puts forth a model of game design in which the designer identifies the feeling they want to evoke first, and the rest of the game design process is guided by that.

Of course, not every game has a story, and defining what should be considered a game was one of the earliest disputes among scholars of game studies, and as new forms of games are created this definition must be constantly reevaluated. I enjoy Spider Solitaire and Word Streak with Friends as much as the next GenXer, but when it comes to academic objects of study (OOS), I prefer games that have story as a central element. My ultimate goal is to create games that will teach critical thinking and research/documentation skills, and the best way to do that is by getting the player (student) invested in the story being told. To be successful, the game mechanics have to seamlessly fit the setting and convey to the player what is important, what their goals are, and how to achieve them.

As a secondary approach to study, I somewhat reluctantly align myself with feminist theory. Gender is something of an elephant in the room when it comes to video gaming in particular, whether it deals with who plays what kind of game, design for specific demographic groups, or the industry-wide collective dumpster fire that was Gamergate. As designer, I want to believe that the games I create can be enjoyed by anyone regardless of gender; as a scholar, I know that we have not yet evolved as an industry or a subculture to the point that we can be blind to something that is so divisive in the games and communities I study. To understand the way we play and use games, we first have to understand who “we” is, and gender differences are relevant to this; thus, applying feminist theory will give important insights into the way we play, design, and criticize games.

Pink, Harrison. “Can I Borrow a Feeling?” Gamasutra.com, 3 Mar. 2013. Web. 14 Oct. 2016.

Hartshorn, Jennifer, Ethan Skemp, Mark Rein*Hagen and Kevin Hassal. Vampire: The Dark Ages. Clarkston, GA: White Wolf Publishing, 1996. Print.

Additional Readings:

Extra Credits’ episode on Harassment addresses the issue of bullying in the gaming community, and while it predates Gamergate, the victims of harassment in and out of the game are often women.

Quantic Foundary examines what type of gameplay is most interesting across genders and ages, and finds that the desire for competition is a higher priority for male, younger gamers, while strategy games appeal to people across all age groups and genders.

Vampire: The Dark Ages (1st Edition) is my most well known game, and adjusts the mechanics of the basic Vampire game to fit a different setting. In it, we sought to make the mechanics and the setting/story meld seamlessly, which shapes my approach to both ludology and narratology.

Wraith: The Oblivion (2nd Edition) was the first game I developed. Well, not entirely true – first edition is now out of print, which was my game; the second edition was developed by my successor, Richard Dansky. It’s far from the perfect game, but it’s not bad for someone who was new to design.

The Only Guide to Gamergate You Will Ever Need to Read is the Washington Post’s summary of the scandal that rocked the gaming industry and pulled back the covers on the widespread misogyny within the industry and the subculture.