Because the field of Game Studies includes scholars from many different disciplines, the methods and theories of research are as varied as the approaches. It is, therefore, impossible to select a single theory or method of analysis as being dominant. A mathematician who studies their field’s version of game theory may focus on probabilities, analyzing the game engine’s method of determining failure or success in any given conflict. An economist may look at the out-of-game impact of Korean gold farmers on both the in-game and out-of-game economies. Sociologists have found fertile ground in gaming communities to study how the anonymity of online gaming impacts harassment, or how in-game gender effects interactions among characters. All of these are equally legitimate and authoritative within their own communities, and it is evident from the way that game scholars reference work in other fields that it enriches the interdisciplinary nature of the field. However, it seems that the “home” discipline from which a scholar approaches game studies largely determines what methodologies and theories they will apply to their chosen objects of study. While Aarseth’s dream of a “native” theory of game studies, divorced from its component fields, is not realized, we have traveled further in recent years than it seemed possible at first.

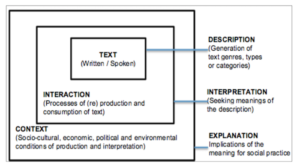

Of course, my own approach is grounded in English Studies, so the same theories common in analyzing literature are often applied: semiotics, discourse analysis, Marxist-tinged analyses of economies of power relationships, feminist or queer theory approaches to the gender of players and characters alike, and many more. Discourse analysis is one useful tool for studying interactions within games, and the way those interactions shape the player’s experience of the game world. Although Hendricks’ “Incorporative Discourse Strategies in Tabletop Fantasy Role-Playing Gaming” focuses on tabletop RPGs, he uses Fairclough’s model of discourse analysis to explore the way that players interact to collectively create a narrative, codeswitching between player and character speech and adopting an almost improvisational “yes and” approach to world building. Similarly, Bourgonjon, et al utilize Burke’s Pentad of dramatic analysis to explore meaning-making and narrative, also drawing on Bogost’s procedural rhetoric as a means of analyzing how game mechanics communicate meaning to players, and the ways designers can use mechanics to steer players down a particular narrative path.

As a woman who is both a player and a designer, I am not blind to the impact of my gender on my own experience, and the experience of other women who play and create games. As a result, a feminist critical perspective can also provide important insights into gaming, as a player, a designer and a scholar. While studies have reported similar results on what percentage of all gamers are women (48% in 2014 according to a Wall Street Journal article, and a 47:53 female to male ratio according to a 2012 Entertainment Software Association survey), a level of harassment and sexism exists in the gaming industry that is shocking enough that it has made national news, in the form of “Gamergate”. But for all the women who play games, and the amount of outrage on social and mainstream media, there

remains a paucity of clearly feminist-aligned game criticism (as opposed to cultural criticism) in the field. Shaw’s Gaming at the Edge: Sexuality and Gender at the Margins of Gamer Culture , for example, addresses gaming from the perspective of cultural studies and feminism – essentially, studying gamer culture but not games themselves. Due to a host of cultural factors, men and women may experience gameplay, and certainly experience game culture, in different ways. Even if my own work does not explicitly address gender, understanding the feminist criticism that exists – and the reasons why there is not more of it – will inform and enrich my own scholarship.

Part of what makes Game Studies such an exciting field is the depth and breadth of disciplinary approaches to the objects of study. As a scholar of English Studies, and one with an especial interest in utilizing games as a tool to teach the skills underlying effective writing – critical thinking, research, and communication – the tools I use will no doubt be heavily influenced by my own background as a scholar of literature and a practitioner of writing education, and as my own studies deepen into composition pedagogy, I look forward to adding those theories and methodologies to my tool box as well. If anything, the sheer range of approaches makes the field somewhat intimidating, but the multiplicity of perspectives and approaches means that the field of game studies will continue to evolve alongside the games themselves.

References

Entertainment Software Association. “Essential Facts about the Computer and Video Game Industry.” 2012. Web. 16 Nov. 2016.

Grundberg, Sven, and Jens Hansegard. “Women Now Make Up Almost Half of Gamers.” Wall Street Journal 20 Aug. 2014. www.wsj.com. Web. 16 Nov. 2016.

Hendricks, Sean Q. “Incorporative Discourse Strategies in Tabletop Fantasy Role-Playing Gaming” in Gaming as Culture: Essays on Reality, Identity and Experience in Fantasy Games (eds. J. Patrick Williams, Sean Q. Hendricks and W. Keith Winkler). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. Inc, 2003. Print.

Further Reading – Feminism and Game Studies

Pop culture website The Mary Sue on applying feminist criticism to video games.

For a very different perspective, check out Breitbart’s article on “Feminist Bullies Tearing the Video Game Industry Apart”.

Gaming journalist Anita Sarkeesian’s video on the Feminist Frequency website criticizing female depictions in video games led to her receiving death threats at the height of the Gamergate scandal: