Pink, Harrison. “Can I Borrow a Feeling?” Gamasutra. 2014. http://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/HarrisonPink/20140303/212088/Can_I_Borrow_A_Feeling.php

While Harrison Pink’s article is written from the perspective of a designer as opposed to a purely academic critic, his practical and pragmatic approach is informed by years of successful game design, as well as an academic grounding in the MFA program in Game Design and Development at the Savannah College of Art and Design, placing him among the rare designers who can speak to both theory and practice with equal credibility. His design process is very similar to that used by designers at White Wolf, a primarily tabletop roleplaying game company where I worked in the mid-1990s, which made it of particular interest to me.

At the SIEGE 2016 conference in Atlanta, Harrison Pink gave a presentation titled “Crafting an Experience: Designing a Game Feelings First.” It was a slightly expanded version of an article he published on the Gamasutra website in 2014, prior to his being hired in his current position at Hangar 13 Games. In both, he presents a new perspective on one of the ongoing debates within game studies – which is more important (or, alternately, which comes first): mechanics or theme?

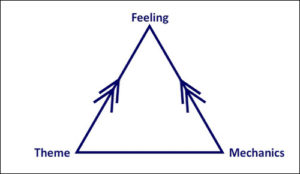

Successful games have been developed that began from either choice, though each presents its own challenges. Pink suggests that rather than starting from either of these, the designer should instead start with the question of what feeling(s) they want to elicit in the player. Ultimately, feelings drive engagement, and engagement leads to continued play and increased enjoyment. Pink states that, “Every design begins with the goal of evoking a specific feeling from the player. A game uses both the theme and mechanics to evoke that feeling.” Whether you prioritize story or gameplay more (and most successful AAA titles include both), an understanding of what feeling you want to elicit from the player will guide successful development of both.

Pink references the widely praised MDA model of game design explored in “MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research” by Hunicke, LeBlanc and Zubec, which focuses on Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics. In it, the authors explain that the order in which designers create games using these elements is the opposite of the way that players experience games. In his piece, Pink reframes dynamics as theme, and feeling replaces aesthetics. However, as seen in the triangle diagram above, Pink’s model does not fit the linear format of the MDA framework. This is a somewhat misleading equivalency; dynamics are significantly broader than specifically theme, and have a clearer relationship to mechanics. Likewise, aesthetics can and do strongly influence the feelings that are generated as a result of gameplay, but it would be inaccurate to imply that mechanics and theme create aesthetics. Pink’s reinterpretation of the MDA model, while dealing with similar components, reinterprets the design process and does not address the player experience.

Although I don’t believe that the game design process can ever be entirely simplified down to three components, Pink’s model is a useful one. In many, if not most circumstances, one of the primary drivers for the creation of a game may be market analysis and business expediency, which can lead to early determinations of elements of theme, mechanics, or feelings (though given that the latter is not as easy to quantify in a business analysis, it is less likely to be a stated objective). These business requirements place expectations and restrictions on the development process. Constraints can spur creativity, though, and these requirements may lay out a framework, but the design process is necessary to go from business objective to game concept.

The value of player engagement, and the study of how to create that connection between player and game, is one of the great challenges facing the industry right now, and is an important foundational concept for my own interest in creating educational games. Designing “feelings first,” as Pink puts it, gets the player invested, and students who are engaged with material can achieve mastery much more quickly than if they are learning out of a sense of obligation, resentment, or the threat of failure. Whether or not the reader buys into Pink’s vision of the design process or the more traditional MDA model, his argument about the value of feelings in determining a player’s enjoyment of a game provides an important missing piece in the ongoing struggle between story and mechanics.

Further Reading (and Watching):

From Stanford University’s Interactive Media and Games Seminar Series, Katherine Isbister from the Center for Games and Playable Media at the University of California, Santa Cruz discusses her book, How Games Move Us: Emotion By Design

Wired‘s “Her Story and Papers, Please are changing gaming forever” describes two recent games that are designed to evoke strong emotions in the player.

EDIT: Late breaking addendum! SIEGE just posted a few of their sessions online, including Harrison’s.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IJ7pljOIO9Q&feature=share