Hendricks, Sean Q. “Incorporative Discourse Strategies in Tabletop Fantasy Role-Playing Gaming” in Gaming as Culture: Essays on Reality, Identity and Experience in Fantasy Games (eds. J. Patrick Williams, Sean Q. Hendricks and W. Keith Winkler). (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. Inc, 2003).

While the majority of my articles thus far have focused on computer-based games, the bulk of my own gaming experience is actually with other forms of gaming – namely tabletop roleplaying games and live roleplaying games. While video games rely heavily on the use of graphics and sound created as part of the game’s programming to establish the atmosphere, tone, and environment, a tabletop roleplaying game (TTRPG) is played, as the name indicates, by a group of players sitting around a table. One of the group members is the Game Master (or GM, sometimes also referred to as Dungeon Master or Storyteller), while the others are players. Random number generation to determine success or failure at combat and other challenges are determined typically by dice, but the bulk of the work to create the game’s world, all communication among characters, as well as communication between players and game master to say what actions the characters are taking, are accomplished through

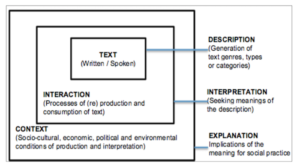

speaking and listening. As a result of this, TTRPGs are particularly well suited to using critical discourse analysis (CDA) techniques to better understand the shared world – and therefore consensus – building among the players.

In Sean Hendricks’ “Incorporative Discourse Strategies in Tabletop Fantasy Role-Playing Gaming,” he uses critical discourse analysis, but also post-structuralist theory to examine the way the participants work collaboratively to create a narrative. While video games, including massively multiplayer online roleplaying games (MMORPGs) are frequently competitive, setting player against player (PvP) as well as player against the environment (PvE), tabletop games are typically primarily played with a team of player characters going up against obstacles and foes created by the game master. Hendricks explains that post-structuralist analysis and CDA are predicated on the assumption that “elements of the social space, such as organizations, institutions, social categories, concepts, identities and relationships are determined by language use” and that “individual selves and identities are constantly restructured and repositioned through discourse” (40). As such, TTRPGs and the accompanying books that serve as source material are, perhaps, even more fertile ground for exploration from an English Studies perspective than are video games, given that the world building is collaborative among a group of people, and is created entirely through language, rather than computer graphics.

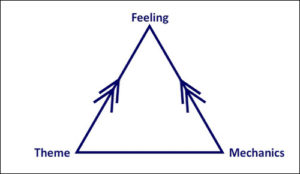

To put TTRPGs into the contexts I have previously explored in game theory, there is an undeniable emphasis on story, and game mechanics serve purely as a means of conflict resolution when character abilities that involve interaction with obstacles or antagonists arise. There is no game engine to govern movement, for example; the player describes the character’s actions. As such, games of this sort have ludological elements, but are often slanted very heavily toward narrative. Within that, there are games that skew further to one side or the other; Warhammer was

primarily a miniature combat wargame that eventually evolved to have a roleplaying component as well. On the other side of the spectrum are White Wolf’s aptly named Storyteller system games, including Vampire: The Masquerade, Wraith: The Oblivion, and others.

The analytical part of Hendricks’ article analyzes selections of a voice-to-text transcript of a gaming session in which he was the game master, and there were four players. He provides examples of using “discourse to create a shared culture, or set of beliefs and understandings about the fantasy frame” (43), and explores the linguistic repercussions of the way players switch between first- and third-person pronouns when describing their actions, as differentiated from and contrasted with in-character speech. Hendricks address this, stating that “the ambiguous usage of ‘me’ and ‘you’ by players during game play indicates a blending of player and character that can signal a level of extension by the player into the game world” (41).

Even the game’s mechanics and setting are learned through language, often by reading rulebooks and players’ guides which often dwarf the kind of documentation provided to players of computer games, where visual cues and the kinetic experience of interacting with a game controller of some kind allow the player to learn-by-doing, without necessarily translating their observations and actions into written or spoken language. Surprisingly, perhaps, the amount of scholarship on TTRPGs is small in comparison to what has been written about video games, although the comparative popularity of computer games, as well as the sheer economic weight of the industry compared to tabletop games is doubtless a major factor. Prior to the turn of the millennium, games were often not seen as appropriate objects of study for academics beyond the occasional social scientist. However, TTRPG gameplay may prove to be a fertile area for study for those who wish to approach computer game design from an English Studies point of view, or on its own as a way of examining the collaborative process of world building, immersion and engagement.

Further Reading:

For anyone unfamiliar with TTRPGs in general, Crash Course has an excellent 10 minute video explaining the concept, as well as some of the colorful history of the hobby.

James Wallis’s “Making Games That Make Stories” argues that in TTRPGs as well as computer games, “the essential plot and structure of the narrative is predetermined before the game begins and cannot be altered” (para. 1). First published in 2007 in Second Person: Role-Playing and Story in Games and Playable Media, it is reproduced in full on electronicbookreview.com.